As we know, 95% of mobile F2P games are unprofitable. After working on 80+ mobile projects with 30+ game teams, I’ve seen these odds play out first-hand.

It’s quite understandable. Building a modern mobile game product is no easy feat! There are an intimidating number of ways to screw up, including code, content, servers, 3rd-party integrations, QA, device OS fragmentation, live operations, community management, customer support, and plenty more.

All of that said, when it comes down to it, most of the product failures I’ve seen have resulted from just a few common, but pernicious, mistakes.

In this short series of articles, I’ll share my insights on a few of the most common reasons why mobile games don’t reach profitability.

To kick things off, let’s start with my personal favorite:

Part I — Start development without a clear business case

“So we have a really cool game idea…” -Fictional Game Developer

We’ve all been there. We have this amazing idea for a game. We’re excited, we’re creatively invested. The team is excited too!! The idea begins to take on a life and momentum of its own…

While this sounds like a dream come true for many developers and creatives (including yours truly), the harsh reality is that a project that starts this way has a vanishingly low chance of success.

The reason is simple:

The market wants what it wants, not what we want.

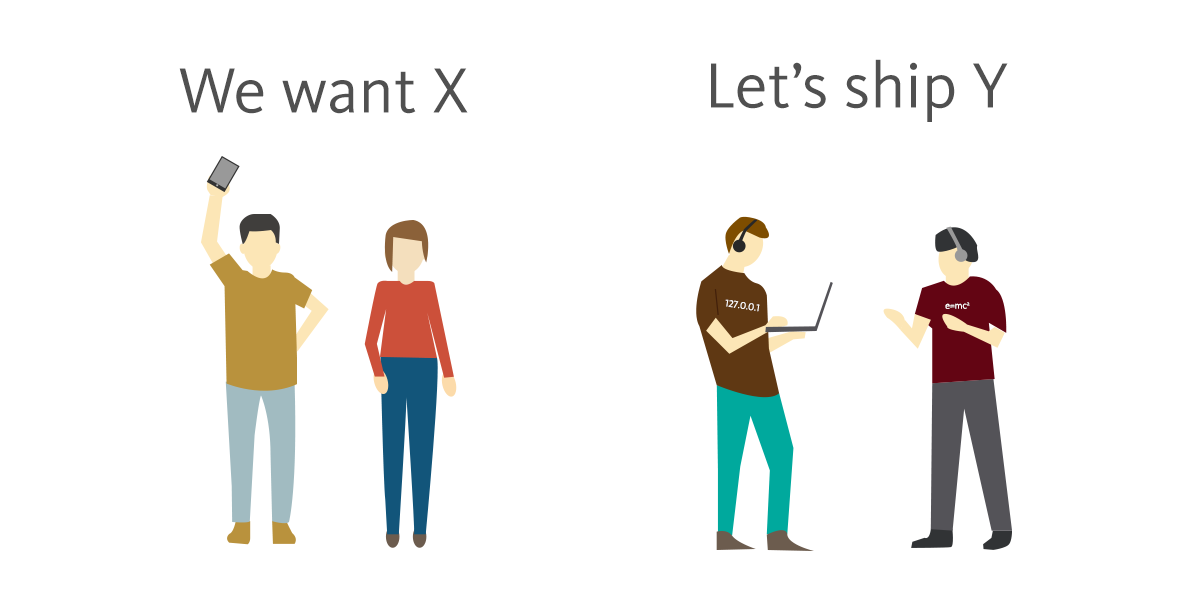

The natural gulf that can exist between our instincts as developers and what the market actually wants tempts us to make this common mistake: starting development without a compelling case for product/market fit.

Quoted from a highly recommended article:

“The #1 company-killer is lack of market… Product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market… Conversely, in a [bad] market, you can have the best product in the world and an absolutely killer team, and it doesn’t matter — you’re going to fail… You’ll [struggle] for years trying to find customers who don’t exist for your marvelous product, and your wonderful team will eventually get demoralized and quit.” — Marc Andreessen

The tendency for us creatives to focus on what we like — rather than what the market wants — is certainly not unique to our industry, or even to creative fields. Stock traders can fall into the same trap when enamored with a hot new tech stock. They forget that in a complex market there is no relationship between their level of excitement and a stock’s performance. They fall prey to classic confirmation bias and go searching for data that will validate what they feel to be true, disregarding the rest.

In the stock trader’s case, one solution is to begin with a methodical ‘top-down’ process, to use a set of rules to filter through thousands of stocks in the market to identify the few opportunities that others may have missed; stocks that might currently be undervalued. The result is a small list of potential opportunities that can then be vetted individually with a cool head.

Opportunity Hunting: A simple example

We can apply a similar, top-down approach to finding potential opportunities in the game market.

Perhaps we could start with F2P market segments that have particularly high engagement and revenue, yet few serious competitors. For example, depending on your risk profile, you might look for segments with greater than 5 million monthly active users, more than $1 average revenue per monthly active user, and fewer than 5 competitors.

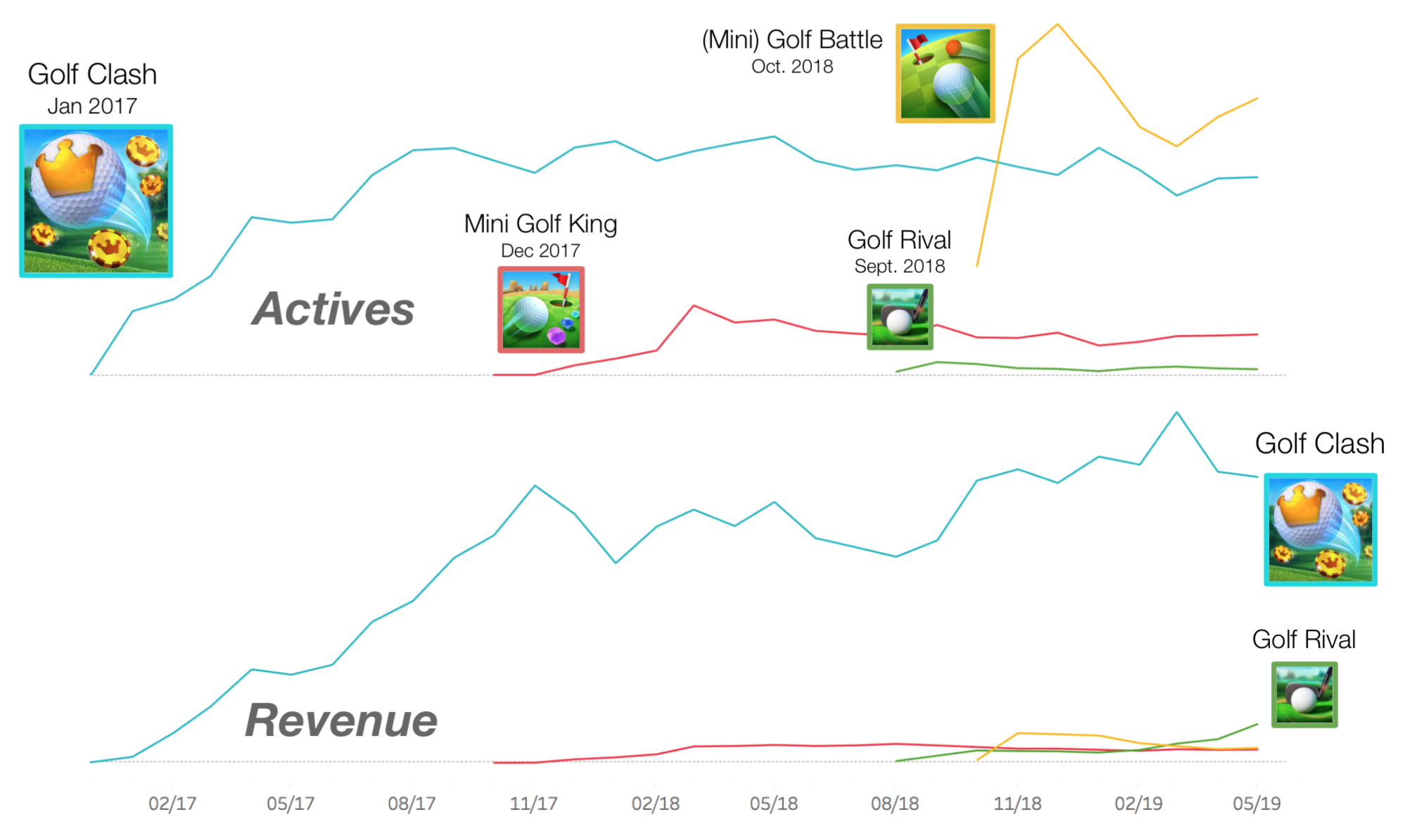

One such category in April 2019 was Multiplayer Golf / Mini-Golf, where only four games drove 13M MAU and $16M of revenue (or $1.23 per MAU): Golf Clash and Golf Rival (by Playdemic and GR Sports), and the mini-golf-themed Golf Battle and Mini Golf King (by Miniclip, PNIX).

With only four major competitors, perhaps there is room for a new product offering a superior experience to those 12M players.

A quick look at the MAU and revenue timeline above tells us that the two golf games are growing and driving revenue, while the two mini-golf games are not, despite relatively comparable quality and features. We could hypothesize that multiplayer mini-golf might have a product/market fit problem, and decide not to focus there.

Digging deeper into Golf Clash and Golf Rival, we’d want to understand what the current players value, their likes/dislikes about the current offerings, whether the category is growing, and whether your team’s strengths and interests could give you an advantage in the space. We’ll leave it there, as each probably merits an article of its own.

Another category meeting our criteria in April 2019 was Classic Poker, where four competitors collectively drove 7M MAU and $15M in revenue ($2.10 per MAU): Zynga Poker, World Series of Poker, Pokerist and Playshoo Texas Poker (by Zynga, Playtika, KamaGames and Atrix respectively). The category leaders, Zynga Poker and WSOP launched in 2010 and 2013 respectively. Could this market be disrupted by a newer, fresher product? Could there be a market for a “ Poker Clash?”

This would only be the very beginning of each hypothetical investigation, but you can see how a top-down approach mitigates creative bias in decision-making. Starting with what the market wants, we identify a set of potential opportunities. Then, by evaluating a group of opportunities — instead of just one — we can avoid creative attachments at this early stage.

But what about creativity?

Creativity will always be a part of game development, and I certainly don’t mean to suggest that you should never take risks on creative ideas. But, because more innovation generally means more risk, it’s important to be mindful of how much risk you are taking on, and how much you can afford.

Bringing a high-budget product to a competitive market involves (quite literally) winning a high-stakes bet. And, if we want to stay in business, we should do everything that we can to stack the odds in our favor.

Two great ways to manage risk:

- Only place bets where we know a proven market exists, and

- Only place bets where our team’s unique strengths give us an unfair advantage over the competition.

“But SuperCell doesn’t do it that way!”- Hypothetical Developer

There are certainly some companies that specialize in taking bigger risks with more-innovative moonshots. SuperCell chose to organize their company around this concept from day one, and their early successes with Hay Day and Clash of Clans (launched just months apart) put them in the financial position to double-down on that strategy.

In other words, SuperCell has the cash to build and test tons of ideas, and just let the market (and internal testing) decide which survive. Most of their projects are killed before launch. Product/market fit is still an essential part of their vetting process; they can just afford to embrace a very high failure rate.

Unless you work at Supercell, your team is probably operating in a different financial reality, one where you can’t afford to kill 80% of your titles in beta. You probably need to be less risky.

“But we don’t want to make clones!” — Fictional Developer

The good news is, we don’t need to! Once we really understand the needs of our chosen market, there is plenty of room for innovation, creativity and passion in how we seek to build a better game for that audience.

To summarize:

- If you are starting a new project, ask yourself: Is your explicit mandate to take a moon-shot, where the most likely outcome is that you’ll pull the plug before worldwide launch?

- If your answer to #1 is no, don’t just START with an idea.

- Start from an existing, specific market where A) size and revenue are easily measurable, and B) you can serve that market better than the competition.

- THEN, deploy your full arsenal: innovation, passion, and the unique strengths of your team to create a product that will be preferred by a large slice of that market.