The topic of Spend Depth comes up often with my free-to-play, mobile game clients, so I thought I’d share some high-level thoughts on the topic.

To start, spend depth means exactly what you think it means- the depth of spend that is possible in your game, for your most committed spenders. In other words, if a hypothetical player sped through your game, spending her way through every barrier, collecting every piece of rare content, and (potentially) becoming the most powerful player, what might that cost?

Because the top 10% of spenders generally contribute 50% of an F2P game’s IAP revenue, the product’s survival depends heavily upon how deep the rabbit hole goes for those top-spenders. For this reason, top-grossing F2P games can have spend depth in the millions.

Some of you may wonder, how on earth could a game have that much content to buy?

We’ll tackle that subject next.

Understanding Free-To-Play Economies

In order to generate such spend depth, Free-To-Play games are typically designed (for better or worse) on the shoulders of a robust simulated economy, and one having the express purpose of efficiently generating bite-sized, intermediating goals (often by the thousands) to slow player progression through your main content. ‘Need more wood to upgrade your castle? You can get that wood faster by upgrading the lumber mill, which costs iron ore!’ etc. You know the drill.

Above: Empire and Puzzles uses a robust town-management economy to slow player progress through the main campaign.

———————————————

These economic simulations can be quite literal (you’re managing a farm business), or more abstract (I’m saving resources to convert into experience points for a hero, so that I can get stronger).

The core building blocks of these economies haven’t changed much since the FarmVille days:

- Addictive Achieve-Reward Loop: The player experiences rapid cycles of goal achievement and reward.

- Periodic Progress in Main Content: The player, with some frequency, encounters new content, in the form of art, story or game mechanics. She might progress to a new environment, unlock a new character, or advance a step a in lightweight story.

- The Grind: Time gates are gradually introduced (you must wait to accumulate resources) and/or power gates (you must get stronger first!) to slow the player’s progress through #1 and #2 above.

- Monetization: The player is able to pay, in various ways, to skip The Grind, satisfying her need to restore momentum.

- TONS of Goals: An effective economy can efficiently deliver months to years worth of runway for the player to perform #1-4.

Note that, because the beating heart of many F2P games is a robust economic simulation, game progression and economic progression are often codependent and must be designed together. This is why it’s usually difficult and/or costly to effectively convert an existing premium product to F2P, or snap a F2P economy into an otherwise premium game model. That said, we’ll set that aside for now; perhaps an article for another day.

Example: Empires and Puzzles

Returning to the topic of spend depth, let’s next illustrate its relationship to free-to-play economics, by looking at a concrete example.

Empires & Puzzles, a top-grossing game (mid-core audience but with a casual, unisex tilt), combines two popular economic models: Town-Management with Time-Gating, and RPG Hero Collection / Progression, with Power-Gating.

Empires and Puzzles (“E&P” henceforth) has a single-player campaign with 300-ish colorful puzzle levels with enemies to battle, plus the typical competitive social / guild modes. All of this playable content serves the primary function of power-gating the player (i.e. “You’re not strong enough for this yet!”), forcing the player to spend most of her time engaging with the character upgrade and town-management economies.

There is also a smaller equipment economy, themed as troops, but we’ll set that aside for simplicity.

In E&P, you overcome each power gate in the main campaign by upgrading your team: acquiring new heroes and upgrading existing ones. To do so, you’ll need a steady flow of several resource types, each slowly manufactured in your city (time-gating). The role of the town-management economy, though obfuscated by layers of resource trading, city-building and upgrading, is merely to dispense xp pellets for your power-hungry heroes.

The Character Power and Town Management economies conspire together to generate thousands of economic goals for the player to achieve, allowing the game to succeed despite having a comparatively modest amount of actual hard content (art, puzzle levels, heroes, enemies etc).

It’s all about efficiency.

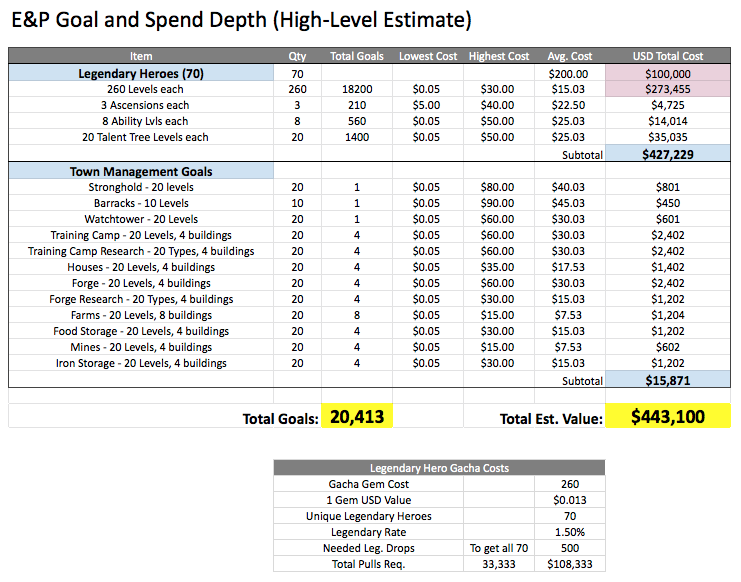

In the Spend Depth chart below, we’ve listed the player goals in each of these main economies and a rough estimate of what a paying player would need to spend to skip them. This is done simply by multiplying average cost of each type by its quantity.

Notice the bold numbers highlighted in yellow. Empire and Puzzles has a goal depth of well over 20,000 distinct goals for players to complete. A particularly motivated whale, sprinting through all of this content, could potentially spend more than $440,000 in total. This is my rough estimate of spend depth for the game.

Evaluating the (blue) subtotals for each content category, notice that the Legendary heroes and their individual, hero level-progressions have dramatically outsized value relative to the rest of the economy, and note that the value of the hero level-up goals (pink) exceed that of the heroes themselves. This feels unintuitive at first, but is simply a matter of raw quantity.

Collecting all of the Legendary-Grade Heroes can be thought of as 70, very expensive goals (requiring ~ 500 gacha pulls, or $108,000).

Even so, with 260 levels per character, these 70 new characters arrive factory-sealed with 260 * 70 = 18,200 new goals to complete, carrying a total price tag of at least $270,000.

So, the very basic spend depth chart above can often highlight opportunities to impact spend depth not obvious at first glance. It can also help us, for example, weigh the potential benefit of adding 10 new characters vs. adding 10 new levels to all existing characters. It’s a simple but valuable tool for F2P Designers and Product Managers.

Designing for Spend Depth

If we were asked to add a new feature to E&P, with spend depth as the primary objective, a good choice to consider might be the use of duplicate character fusion (sacrificing a duplicate of a character) to raise that hero’s level cap by five, and, say, up to two times.

Theoretically, this should increase spend depth substantially, at minimal development cost.

Finding a duplicate Legendary character costs roughly $15,000: $3.25 per Epic Gacha / (1.5% chance of Legendary) / (1/70 chance of the right Legendary) = $15,166.

Doing it twice for a specific character would cost $30,000. Doing so twice for each of a whale’s ten favorite characters? ~$270,000, plus the cost of actually attaining the 100 levels that you unlocked!

Takeaways

When designing any F2P game, or when adding features or content to an existing one, I’ve found this to be a useful framework:

- Make sure you have the necessary amount of hard content (new environments, characters, challenges) to reward player progress and keep things exciting. That said, be judicious, as this is often your most limited resource.

- If possible (given target audience), use both time-gating and power-gating to control the pace with which the player consumes your hard content. Power-gating opens the door to hundreds or thousands of intermediating, stat-based goals (level-ups, talent trees, equipment, etc.) and time-gating limits how quickly the player can move through them.

- Further increase spend depth by using a goals table to identify a) where new goals or features might be added at low cost, and, in particular, b) where goals can produce geometric gains, e.g. through repetition of existing goals (collect duplicate Legendary characters) or by adding goals that apply uniquely to every unique copy or variant of item, character, building, or other primary asset.

Of course, each of the thought experiments above assume that, as a starting point, you have a fun core game experience that’s worth playing. If the game economy is part of the engine under the hood, you still certainly need seats, a chassis, a nice coat of paint and some fun places to go.

In other words, while economy spend depth cannot and should not be the only factor impacting your product decisions, it certainly deserves some thoughtful consideration.